So I got my permanent site assignment and about a week later I went for a 3 day visit. Another member of my team who was placed nearby went with me and we stayed with a member of Group 84. I went to my school for a day, met my principal and co-teachers, saw my library, saw my house being built, met my host mother, visited the resort in my village, had many thoughts and feelings then came back to the training village. About a week before we were scheduled to move to our sites, one of our project coordinators told me she needed to talk to me after sessions. “Don’t worry, you’re not in trouble and it’s a good thing!” she reassured me. The session finished and lunch began and I sat down with her and another staff member. “We’re changing your site,” she said, matter-of-factly. Apparently there had been a lack of coordination between my host family and the school committee and they were unable to finish building my house, despite having 3 months to complete it. My new village was on the south coast of the same Island (Upolu) but on the west side instead of the east, about a 15 minute drive from my friend who had gone on my original site visit with me. My new school was very small – only about 75 students and 4 staff members. My host family would be just an older couple, and I would be living in a room in their house. I sat and listened with my heart pounding, trying to ask intelligent questions to gather all important information, and feeling so many contradicting things that they all cancelled each other out and I remained quite calm. It sounded like their reasons for moving me were good ones. I chose to be hopeful. I was very happy to be so close to my friend.

Our last week of training finished in a whirlwind. We packed our things and all the new things our families had showered on us, most of us 2 or 3 items of luggage heavier than when we’d arrived. The village bundled us off with tremendous angst and fanfare. My host mother cried every day for a week leading up to our departure. (She cried more before I left for my 3 day site visit than my own mother did when I left for 2 years.) With half the village chasing the bus as it drove away, I took a deep breath and thought things and felt things. We arrived in Apia for another whirlwind of final training sessions, Thanksgiving and our Swearing-In ceremony. We did our best to shop for homes we’d never seen. In stolen moments of free time, we clung to each other. “When we get to Apia, can we just cuddle and listen to music?” one of my friends had asked. This was our last chance to be together, to dress and act like westerners, to feel comfortable and familiar and normal before we would suddenly be starting over again. From scratch. Alone. So we cuddled and listened to music. We drank a little and we talked a lot and we slept hardly at all. Some of us went out quite a bit, thrilled to be out from under the restrictions of the village, but a few of us just wanted to stay in, eat ice cream, drink whiskey or wine, and watch movies (but we always just ended up forgetting to start the movie.) Those who went out would wander by the staying-in room on their way back and would stay for a drink and relay their going-out adventures.

I heard a rumor on Wednesday of that week and found out for sure on Thanksgiving that my housing situation had changed again. I was still going to the same new village, but instead of living with the host family, I would have my own house on the school compound. My new host family lived next door. Apparently the village had strong thoughts and feelings about my coming and felt that I should belong to the whole village and not just one family. Living at the school, more people could look after me and get to know me. They were in the process of fixing up said house for me – adding an indoor bathroom and shower and all the Peace Corps required safety features (screen wire on the bedroom windows, deadbolts on the doors, etc) and it wasn’t quite finished yet. I may have to stay with my host family for a few days until it was ready. Deep breath. Stalemate of feelings. Be calm, be flexible, be excited: own house! Be realistic: own house…eventually. And then I carried on with Thanksgiving. We were sworn in the next day, and the day after that we dispersed with hurried hugs and poorly concealed tears.

The safety and security officer drove me to my village instead of having my host family come pick me up because she wanted to inspect the work on the house. It was not finished, of course. They had only been given about a week’s notice of my arrival, which actually made their progress quite impressive. They had accomplished more in their 4 or 5 days than the other village had managed in 3 months. They were very motivated. It was a good sign. But it would be a few days before I could move in. They drove me and my piles of things next-door to settle me temporarily in the most finished bedroom in my family’s house. My host father is the village carpenter and had abandoned work on his own home to work on mine. “My” room (and I’m still not sure who I usurped in order to stay there) was in the very front of the house with one window looking out on the main road and the other onto the porch with a clear view through the always-open front door into the living room. The bedroom door had no latch, but the S&S officer instructed them to install a lock the same day since I would be keeping all my things in the room. The windows had curtains of sheer lace. The bathroom was outside behind the house, with a door that did not latch, and the shower was a solitary pvc pipe sticking out of the ground. (That afternoon they built a little tarp shelter around it for me.) My new family was not just an older couple. In the weeks that followed, I counted and discovered that in fact 19 people live there. The first night it may well have been a thousand. After dinner, I locked myself in the room, hung lavalavas over the windows and tried to hold down the panic. I’ve had moments of doubt every so often since the beginning, but that moment rolled me and wouldn’t let me up for air. I was absolutely convinced I was not cut out for this.

They finished my house and I moved in about 4 days later. It was a beautifully hilarious and very Samoan experience. I’d had my things packed since right after school, but we didn’t actually leave to bring anything over until around 10pm. With the help of my many siblings and a wheelbarrow, we brought everything in one trip. Unfortunately, no one remembered the key to the gate. There’s a barbed wire fence around the school compound. We realized our oversight as soon as we arrived, but like idiots who step onto an elevator and don’t push any buttons, we stood in the dark for about 15 minutes before anyone thought to go back and get the key. Once inside the house, my sisters and brother fussed around washing the teachers’ leftover dirty dishes, putting up curtains, and apologizing for things I didn’t mind in the least and asking over an over again if everything was alright and if I was happy and absolutely sure I would be OK sleeping here alone because someone (or a number of someones) would happily stay with me if I didn’t feel safe. I smiled and laughed and promised over and over that everything was perfect and wonderful and that I felt no trepidation whatsoever sleeping in the house alone. Which I did, blissfully.

The next morning, I had school children sitting on my doorstep at 7:15. Kids show up early for school, here. At the end of the day, once everyone had left, I changed out of my puletasi and began unpacking. I like unpacking under normal circumstances, but this was like being released into the ocean after living 3 months in a wine glass. It started to rain a little. I hit “shuffle” on my iPhone and set it in a bowl on my counter. Regina Spektor started singing. There were a few guys outside putting the finishing touches on my septic tank, but I didn’t care. I wandered around my house putting things away and singing, grinning like an idiot and remembering why I thought this sounded like a good idea 2 years ago.

I was in the village for about two weeks before school let out for the year. In those first few weeks (and even still, but to a slightly lesser extent,) I was treated much like a very expensive, fragile piece of antique furniture. Everyone has very strong opinions about what should happen to it, where it should be, what events it should be present for, who should have custody over what aspects of it’s care and maintenance, etc. But once all of these things have been decided by the Makers of Decisions, and the thing is present at whatever it is supposed to be attending, it is admired for 30 seconds, then mostly ignored. And then someone says, “Oh wait, no look! It can do this cool thing!” and everybody says, “OooOOoohh!” and then they go back to ignoring it. I didn’t mind. Social interactions have always been tiring for me, so being ignored was kind of a relief. Nearly everyone in my village speaks English, so they would address me in English, I would try to respond in my very little Samoan, they would be mildly impressed, would ask me the standard questions: “Is this your first time in Samoa? How do you like it? Do you like Samoan food? How long will you stay here? Are your parents still alive? Are you married? How old are you? And still not married, really? Do you have a boyfriend? Do you want a Samoan boyfriend? (To which I reply with my practiced: “No thank you, too much hassle! Samoan boys are very cheeky!” To which they laugh uproariously and agree with me, “Yes yes, smart girl. Too much hassle.” If you’re a palagi boy, apparently they’re much less likely to take no for an answer.) And then the conversation would be mostly over and they’d go back to talking to each other and I would go back to trying to listen for one of the 8 words I understand and pretending I knew what they were talking about.

And then school was out and I had a few calm weeks of freedom to explore my village, to finish setting up and settling into my home, to figure out how the buses work, where to buy groceries, and to spend long uninterrupted seasons of time each day completely, blissfully, miraculously alone. I could, for the first time in 3 months, use the toilet as many times as I wanted without any one accompanying me, observing me or timing me. After which, I could wash my hands, with soap, in a sink. It was (and continues to be) the epitome of luxury. For most Samoans, being alone is one of the worst tortures they can imagine – I am asked almost daily, with openly expressed pity, how terrible it must be to live alone. I will never be able to explain how magical it is and how vastly beyond anything I ever dared hope. Solitude is a gift, and I constantly resist the temptation to hide within it forever.

Christmas descended like an unwelcome houseguest. Samoans love Christmas, but in a very “Of Mice and Men” kind of way. It is as if they collected all of their favorite songs and traditions from pop culture and Christianity and Christmas and threw them all together in a stew pot along with anything else that struck their fancy, and let it all ripen for a while. They then drilled a hole in the bottom of the pot, and whatever oozed out, they said, “Yeah! Boom! Christmas!” Take, for example, what auditorily assaults you at ear-bleeding levels on every public bus: they will digitally combine upwards of two songs – really just any kinda songs – layer in a reggae-adjacent type beat that sounds like it came free with an early 90’s model keyboard (because it probably came free with an early 90’s model keyboard) and, if they’re feeling creative, write their own Samoan lyrics. The result is the bastard child of early 90’s church music, reggae, gangster rap and Christmas. A few of my favorite medleys have been “The Little Drummer Boy” combined with Eminem’s “Real Slim Shady.” I also heard “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen” mashed up with “Move Your Body like a Cyclone.” Stuck in my head for a whole afternoon once was their re-written, reggae “Hey Jude” about Christmas. It was an unpleasant afternoon.

I decided to mentally skip Christmas this year. It’s been arriving too quickly for me to feel fully anticipatory anyway, so it didn’t seem to be any great loss to just pass a year without one. I knew that trying to watch Christmas movies and play my favorite songs alone in the humidity during summer vacation would just feel sadder and stranger than embracing the new, odd, assuredly memorable, cultural experience I would have for exactly what it was. So I just pretended that this would be something else entirely, and didn’t try to fit any of my round Christmas pegs into this Samoan square hole. And as it turned out, I didn’t really have to pretend that hard.

There are two churches in my village, but they are both the same denomination and therefore “are not in competition with each other” except, of course, when it comes to me. When I first moved to the village, they wanted me to attend one church Sunday morning, have lunch and spend the afternoon with one family, then drive me down to the other church for the afternoon service and dinner with a different family. Then switch the following week. Thankfully, the Peace Corps stepped in and insisted I be allowed to make my own decisions on where I would attend church, that once a Sunday was plenty and that I would probably be taking my Sunday afternoon naps in my own house. They’d grudgingly acquiesced, so for Christmas, I wanted to do my best to split my time and attend events at both churches. The festivities began around 7pm on Christmas Eve. My host brother had arranged for someone to drive me down to the church by the beach for their “Youth Event” which began at 7. My ride arrived at 6, and I thanked them profusely and politely told them I would be ready at 7. They came back at 6:40. (Of course, an event that starts at 7 does not actually really start until 7:15 at the earliest, but probably 7:30 or maybe 8. So, good thing I was early!) The event was a strange sort of performance/competition/fund raiser (as are all Samoan events, I am learning) with apparently very specific rules for audience participation that seem completely arbitrary. Since this is what everyone has done their entire lives, no one feels the need to explain any of it ever, so I get to watch and learn and try to act like I know what’s going on. From what I could gather, there were two choirs competing. Each one would perform 2-3 items: songs, skits, beat poetry, interpretive dance, etc. Then it was the other choir’s turn. There were bowls set out in the aisles for donations, which audience members could walk up and drop in at any time. Some songs received many donations while others none at all, and the distinction seemed to me to be unintelligible. Was it a judgement of the performance? Was it for the encouragement for specific people in different positions of prominence in the number? Any criteria I imagined would be disproven by the next surge of contributors. So just I tried to randomly space my donations to match the whims of the crowd and I’m not entirely sure I didn’t succeed. Several hours in, the choirs joined together to re-enact the Christmas story in great detail, complete with shepherd staffs wrapped in metallic gift ribbon and sequined shepherd headdresses. I recognized Mary and Joseph as the couple who’d very kindly looked after my safe return home when the bus I’d been riding had broken down a week earlier. (I’m getting very spoiled – when the engine began choking and stuttering, I only very calmly thought, “Well, I’m sure someone will get me home.” and I was right, thanks to Mary and Joseph.) When the program concluded around 11pm and all the prizes were given (apparently the choirs were competing in a number of categories, and each seemed to win a fairly even number of prizes which consisted mostly of small kitchen appliances and machetes,) there was great confusion and high tempers over what was to happen with me next. Earlier in the week, I had planned to meet my brother after the youth event to wait for members of the other church to arrive and begin their midnight caroling tradition. They march from one church through the entire village and end up at their church on the main road. The family who’d given me a ride to the youth event were very determined to drive me home, and my brother tried to convince them that we had always planned to stay. (Looking back, the confusion stemmed from the family asking me at 10pm if I wanted to go home and I, believing that I had 2 hours to kill before the next event commenced, had foolishly said yes.) It was Battle Royale of stink-eyes and muttering, like a chain of custody dispute for a key piece of evidence in a murder investigation. No one ever considered asking the evidence what it wanted to do. In the end, I was bundled into the car and driven half way home, at which point I was instructed to get out and get into a different car going the opposite direction and driven back to exactly where I’d just left. I felt a little bit like a Looney Toon, and a little bit bad for not feeling worse that people seemed to be experiencing some genuine angst over the situation.

Back at the beach, I gathered on the road with members of the other church, all dressed in white with shirts and towels wrapped around our heads so we resembled ghostly shepherds in the dark. We began to wander and sing. In the absence of blaring horrendous keyboard accompaniment, Samoan voices are quite lovely – they’ve all been singing since infancy and split themselves into harmonies automatically. Slight dissonances give color and texture to the tone. The round voweled syllables roll over and over each other like tides. It began to rain a little. And suddenly in the heat of the air and the closeness of so many bodies, the coolness of the rain, the words I didn’t understand, the few muffled stars and the voices gleaming in the velvety darkness, walking like shepherds, I felt transported to something magical and mysterious – some deeper truer Christmas than I’d known before.

The magic wore off after about 45 minutes. The rain continued and gradually intensified and still we plodded on. And on. And on. (Do you know what 100 wet plastic flip-flops sound like? I do.) And on. Around 2:30am we dripped blinking into the blazing florescent lights of the church, and suddenly I was vividly aware that my white outfit was now basically clear. The pastor got up to the pulpit looking fresh (he had not been walking with us) and preached for probably about 20 minutes, but what felt like 4-5 hours. And then it was over and my brother asked me if I was tired. I have to be careful how I answer any questions about my preferences. When asked any questions that begin, “Do/would you like (to)…?” or “Do you want (to)…?” and I answer definitively “Yes,” everyone present will tear their lives apart to try to get that thing for me immediately, and then will apologize profusely and with great sorrow if they fail. I’m learning to be very non-committal and to express opinions very cautiously, especially since most of the time, I care very little. But when my brother asked if I was tired, I answered immediately and definitively. “Yes, I am very tired. I can walk home if I have to, but if anyone is driving that way, I would like a ride.” So I was loaded into the back of a truck and driven home. I was in bed by 3.

At 8am the following morning, my phone rang 12 times in a row after which, I heard my name shouted from outside the fence 20 feet away from my window. It was my sister and her husband who needed me to unlock the gate so they could give me tea and toast. When I moved into my own house, I had promised to eat dinner with them every night but I assured them I could handle breakfast and lunch on my own, and other than making sure I am continuously stocked with copious amounts of fruit, they have respected that arrangement. Apparently Christmas is different. “Rina, are you tired?” she asked, taking in my one barely squinted open eye and hair swimming around my face like a sea anemone. “Yes,” I answered, allowing far too much irritation to bleed into my tone, “I was still sleeping.” An hour or so later when I was more awake, I texted my brother to thank her for me, since I was sure I had forgotten in my semi-conscious state. He responded that she’d thought it was funny. At 10am my brother arrived to take me to the “Tausala,” another singing/dancing event that everyone seemed very excited for me to attend. Having heard really nothing about this event other than the name (which I did not bother to look up, but apparently has something to do with breadfruit, or possibly fishing…?) and that it was happening at the main road church, I was ready in my wildly uncomfortable white church puletasi. My brother showed up in jeans. “Why are you wearing that?” He asked. I once again substantially failed at hiding my frustration when I responded, “Because you never told me anything!” but I was relieved to change into something more airy, and he didn’t seem put off in the slightest.

None of the rest of my family came with us. “Where is everyone else?” I asked. “They’ll come later.” He answered. “Then why don’t we wait and go with them?” I asked. “Because it starts at 10!” he said. So we arrived at 10:30 and sat around for 45 minutes before anything happened. Chairs and tables were set up in a circle around the edges of a large open fale next to the church. I was given a seat. Then I was asked if I wanted a better seat so I could see better. I said I could see fine and I was happy to stay where I was. So I was moved to a different seat so I could see better. Some snacks were served. Plates piled with pastries and snacks were served to the pastors, pastors’ wives, the matais and other important guests. Then the rest of us were served 2 bags of chip-type snacks and a cup or bowl of this lovely cold breakfast soup made from scraped pineapple, bananas, coconut water and peanuts. Then the dance numbers began. Several groups (the women’s committee was one, and I’m not sure about the others,) in matching puletasis had planned many dances, songs and skits. Between performances, the band would just play music and anyone could get up and dance. Alcohol is fa’asa (forbidden) in my village, so everyone just got sauced at home before they arrived which made for very entertaining dancing. I was invited/coerced to dance a few times. The donation bowls were, of course, ever present, and several different people throughout the day handed me money to put in. (Apparently the final totals matter much less than the percentage of participation.) Around 2:30 or so when things were winding down, the band played a slower very couple-y type song and the pastors got up and asked their wives to dance. A few other couples joined them, and I actively avoided eye-contact with the world. My sister sitting next to me said, “Someone is going to ask you to dance.” I knew. A strapping gentleman who looked too close to my age for him to be entirely kidding only waited half way through the song before making his way over to where I was sitting. As soon as we stood up, the floor cleared like I’d set off a flash bomb. We danced like junior high and I twirled in my long flowey flowery skirt, and everyone talked about it for days afterward. “Mania le siva, Rina!” (Good dancing) they would say and I would say, “Leai! Ou te siva leanga tele!” (No! I dance very badly!) and they would laugh because I wasn’t wrong. I never learned my dancing partner’s name and he did not ask for my phone number or to be his girlfriend afterward, so he’s OK in my book. I was home that afternoon by about 3:30, I gave my family some jerky as a Christmas present (which my parents thought was too sweet and did not like it until they tried cooking it. After which, they decided they liked it so much that they didn’t let anyone else in the house have any of it) and then I went home and went to sleep for several hours and Christmas was over.

A week later, I escaped to a resort with 3 other volunteers – two boys and a girl, my same “staying in” friends from before. We had grand plans to swim to some caves and go on adventures and leave the hotel, but we did not. We took naps in the afternoon, then we stayed up till midnight, watching “A Mighty Wind” on my laptop. 20 minutes till midnight, we stopped the movie to decide what music we should play leading up to 12:00 and what should be the very first song we should hear in 2014. We found a Philippine soap opera on TV that had a count-down in the corner so we’d know when it got to midnight. We settled on an 8 minute classical piece and started it 8 minutes before midnight, and decided on “Another One Bites the Dust” for our first song of 2014. About 2 minutes before midnight, the timer in the corner of the screen disappeared, and I began staring unwaveringly at my iPhone clock to start a 1 minute timer the second 58 switched to 59. Then at 45 seconds to midnight (not one minute. 45 seconds.) the soap opera disappeared giving us an old-timey movie countdown, complete with beeps.

And then it was 2014. The TV showed pretend fireworks. We popped champagne and hugged and kissed each other and I thought things and felt things and wondered that this would likely be the strangest year of my life and was I even remotely ready for it. No, and yes, then no again. Also yes.) We stayed up talking and listening to many more songs. A Samoan gentleman knocked on our door after a little while and told us that he was staying in the room next to ours and his wife was pregnant and asleep and could he please hang out with us and share his champagne? We said yes, and he stayed for a long time and made fun of our classical music and told us about being in the (I believe) Italian navy and marrying a Romanian woman. When he finally left, we set alarms for just a few hours later. We dragged ourselves out of bed and walked a few minutes down the road to a sea wall to watch the sun make it’s first unimpressive appearance in 2014. The very first in the world. The clouds were beautiful and the breeze was cool. Also, we saw a turtle.

And so it goes.

I eat dinner with my host family every night and I’m getting very spoiled. When I first arrived, they asked what kind of food I liked and I told them that I like everything and I liked Samoan food and liked trying new things and I was happy to eat whatever they were eating. And they asked, “But no, but what do you really like?” So I told them that I really did like everything, “I just have a very small stomach and I can’t eat very much, even if I like it.” And they asked, “But no really, but what do you really like?” “Well, I really do like taro, but it fills me up very quickly, and I do eat meat, but only a little.” “What do you eat a LOT of?” So I gave in and told them that I usually like to eat just a little bit of meat and a lot of vegetables. And now I am horribly spoiled. They don’t seem to care *what* I eat just as long as it is in large quantity. The sister who cooks for the family used to work at the resort before she had kids so she understands how palagis enjoy things. Every night I am served a small amount of meat (usually chicken, taken off the bones for the palagi, or very occasionally beef,) and mountains of two or three of the following: cabbage, tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots, green beans, lau pele (which is a little like spinach,) and once watercress, always with grilled onions. Everything stir fried lightly in oil and salt, never cooked past the point of a little crunchiness. On Sundays for to’ona’i (the large after-church lunch) there will also be a few specialty things like fried fish nuggets (also taken off the bones for me,) lu’ao (my favorite, taro leaves with coconut cream) lobster and/or crab, oka (chunks of raw fish, onions and cucumbers served cold in coconut cream. I had it once with some type of muscles or oysters that they’d treated with lemon juice which gave them a very interesting almost crunchy texture,) and yesterday I tried octopus in black coconut cream. I asked about the color and they told me that it doesn’t taste as good if they remove the ink sack before cooking. If you can get over how it looks, it’s really quite delicious. Since I don’t let them bring me meals for breakfast or lunch, they ensure that my fridge is well stocked with coconuts (to drink) papaya and bananas, and maybe some pineapple or watermelon. I’ve spoken with several other volunteers and for most of them fruit is rare and vegetables are almost non-existent. They closest they come to a green thing is cabbage, cooked to death in a soup. I feel incredibly blessed. At the table with me always is my host grandmother who has only one eye and at 86 is the oldest woman in the village. About half the time my host parents will eat with us as well, and my brother (who lived in New Zealand for 10 years and speaks English fluently) will sit with us so he can talk to me and translate, but he doesn’t eat. My two two-year-old nieces, Litia and Mila (the daughters of each of my sisters) provide the entertainment. They know my name now and will start shouting it as soon as they see me walking from my house. If it is still light out, one or both of them will run out to meet me and hold my hands to walk me in. All of Samoa is clothing-optional for any children ten-years-old and under (and gender neutral – I’ve seen boys in skirts, with pigtails or painted fingers and little girls shirtless in bro-shorts with short haircuts, probably because of lice), so usually the girls will have on either a shirt or dress or bottoms but hardly ever any more than one of those things at a time. While I sit and eat we play any of a number of different games. There is “Sneak Closer and Closer to Rina Until She Makes Eye-Contact, Then Scream And Run Away.” There is also, “Say ‘Rina’ Until She Looks at You, Then Laugh, And Repeat.” There is, “Speak Pretend English” in which they imitate my intonation and we have pretend conversations, not to be confused with “Speak Real English” (usually at the encouragement of one of the older family members,) where they will show me how they can count to 3 or sometime 5. Once Litia and I had a conversations of “No’s”

“No, no no.” she said.

“NOO no no.” I said.

“NO no no no no.” she said.

“Nono nono no.” I said.

“NO NO NO no no.” she said.

And so it went for a while. We laughed uproariously. We also sometime have evil laugh conversations/competitions the same way. Mila is “the naughty one” in that she is louder and less shy and warmed up to me first. She has pierced ears, but lost one of her hoop earrings ages ago, so runs around like a pants-less baby pirate. Tia is hardly “the good one,” she’s just sneakier. She plays more hiding games, poking her head out where only I can see her and making fantastic faces at me. She has terrific eyebrows. Also, she dances. Her grandparents will tell her to go put clothes on, and she’ll obediently run out of sight into the hallway. Then a few seconds later, she’ll sneak back out just far enough that I (and no one else) can see her and do a cheeky little naked dance until she’s notices and instructed to go get dressed again. She’ll disappear again for a minute. Run back out and dance some more. She gains confidence and spunk the less clothing she’s wearing. If you ask her to dance she almost never will. Mila will, but she’s not quite as good at it. Once you stop asking and look away, Tia will dance until you look at her, and then she’ll stop. Don’t even try pulling out a camera. Tia’s one-year-old brother affectionately referred to as “the fat one” has hair like an old man and is the only Samoan baby to have never been terrified of me. Most babies will cry just looking at me, and the rest will stare with tremendous consternation as if to say, “…..but WHY is she so *white*??” But the fat one smiled at me the day we met. I feed the three of them like puppies, giving them carrot sticks or cucumbers off my plate which they eat like candy (even after being dropped on the floor several times.) I doubt they eat many vegetables any other time, so I consider it a win. My host parents speak no English so I do my best with the few Samoan words I have to make them laugh at least once a meal. Usually by telling them they’re making me fat (which they have expressed is their goal) or just saying the word “fat” as a groan at the end of the meal. Or by playing with words to string together strange phrases to talk about the babies. They got a big kick out of “ofu mo le aso fanau,” (directly: “outfit for the day of your birth”) which I said one of the first times a little brown naked body streaked through the dining room.

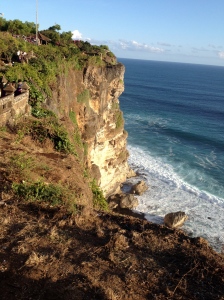

Today I go back to the training village for 2 weeks for Phase II (or Phase 11 as it was mistakenly written on one of our schedules.) We will have more technical teaching sessions, more language, and another week of practice teaching. I’m excited to be all together as a team again, but I am mostly dreading the rest of the experience. I will miss my beautiful little house filled with order and solitude. I will miss my family: my parents who spend so much time being anxious over my wellbeing, my chatty sister who texts me constantly, usually wanting to bring me some type of food, my quiet sister who cooks, and smiles and washes my sheets (“because her hands are much stronger” they told me,) my brother who acts as administrator and liaison for all practical needs – arranging rides for me, helping me catch the buses, carrying all heavy things, taking out my trash, and of course, constantly translating, my little sisters who never speak, just bring me things and stare and smile very shyly with big eyes, and the babies who shriek when I arrive and cry when I leave. I will miss the village, the friends that I have made, the sandy road with the pigs and dogs, and the wild sea at the end of it. Light brown coral with veins and waves of black lava running through and over and around. The arms and legs of rock luxuriate into the tides like a half-full bathtub. My shore is rugged and jagged and treacherous and beautiful. Tiny charcoal black crabs and larger peach-colored ones with 3 red spots on their backs (which are delicious) hide in the pits and hollows. In the pools and around the live reef, tiny fish the color of blue bottle glass hang motionless in unison like bells on a wind chime. When the tide comes in, the water blurs and distorts as the cold mixes with the sun warmed pools. The palm trees lean out over the water to watch.

On the bus on the way to visit my first permanent site assignment, I did battle with my great enemy, Jealousy. Other volunteers were placed closer to town, closer to each other, in better houses, in easier villages with better schools. One actually lives at one of the nicest resorts in the country. So I was sorting out my head and I was struck by the conversation with the fox in “The Little Prince” (Antoine de Saint-Exupéry)

“What does that mean– ‘tame’?”

“It is an act too often neglected,” said the fox. “It means to establish ties.”

“To establish ties?”

“Just that,” said the fox, “To me, you are still nothing more than a little boy who is just like a hundred thousand other little boys. And I have no need of you. And you, on your part, have no need of me. To you, I am nothing more than a fox like a hundred thousand other foxes. But if you tame me, then we shall need each other. To me, you will be unique in all the world. To you, I shall be unique in all the world….”

“I am beginning to understand,” said the little prince. “There is a flower…I think that she has tamed me…”

I sat aching on the wooden bench (the back rest hits you at exactly your most prominent spine, and is set at an angle to induce migraines) gazing out the window at the sweep of green on green with blue above and beyond and I decided that it didn’t matter what my village was like or my family or my school or my students or my house. Annoyance and frustration, success and failure, beauty and heartache and more beauty live in every village. But my island, my village will be the most beautiful – the most important – to me, because it is mine. After two years – after just 6 weeks – it will have tamed me. I will have tamed this place and we will be unique to each other in all the world.